We’ve recently written about how using the right prototyping techniques can save your company a fortune but we didn’t delve deeply into what those techniques are, or how they can be integrated into your development process.

It’s almost inevitable that any form of prototyping will help your project - the benefits are simply too significant. But, like any technique or process, it can be done both more effectively and less effectively. We’d like to introduce you to how we at Fluid UI believe prototyping should be done and what most effective approach is given the normal business constraints of time and budget.

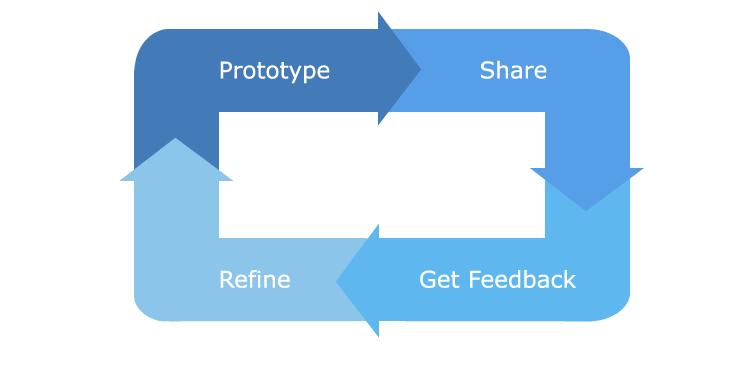

Prototyping at it’s heart is an iterative and communication driven approach to software design. It is based on the principle that no first design will get everything right. Rather, the best path to success is to create, test and iterate using the fastest and most appropriate tools during each iteration. Many of the designers we’ve talked to use upwards of a dozen different tools when prototyping depending on the circumstances and the needs of the task at hand. That said, we feel strongly that you should always start in the same place - on paper.

No other medium or tool comes close to paper’s flexibility or sheer creativeness. Some prototyping tools do a good job in trying to emulate working on paper in a digital form, but at the end of the day, using paper has a beautifully tactile, low fidelity and collaborative feel to it that no screen can ever match. Software tools have a purpose (we would recommend against prototyping using code), but they come later in the design flow when we are iterating with two of the key groups that will define the success of the design - our customers and our users.

At this early stage, painting a picture is worth a thousand words and paper is the undisputed king of quick and easy.

Design is often considered to be as much an art as a discipline and as such, the concept of a successful design is very much based on opinion. This of course begs the question of whose opinion it is that counts most, and the answer to that is twofold - firstly your customers and secondly, your users.

Firstly we must try to understand your customer. Who you customer is will vary significantly depending what your company does. The quickest, easiest way to recognise your customer though is that they are the person that always pays for the project (either directly or indirectly) and by virtue of that, is the person who decides whether it is considered successful or not - regardless of whether they ever actually use the finished product.

In some cases, your customer is also your user, but more often than not, your users are a distinct group of people and must be treated separately. Your users are the people who will use your product every day, learning to love or hate it depending on how well it solves their problems and how easy it is to use. While your customer will sign off on the design, the users are the ones that will define whether it is successful in the long run - whether your hard work continues to see the light of day, or whether it is consigned to the dusty shelves of the software graveyard.

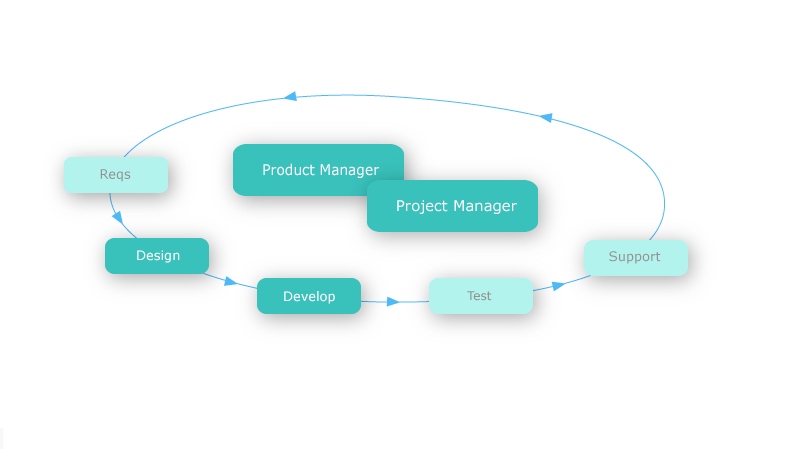

Feedback can come from three separate sources. Firstly, from your fellow designers and developers in your development team, secondly from your customer and thirdly from your users. The best designs come when all three of these groups work closely in tandem but often one, both or all three of these are unavailable during the majority of the design process (e.g. the customer is a remote client who does not work in the office, the development will be outsourced or no budget or time is allocated for user testing).

The more closely you can work with your customer in this initial phase, the more successfully your design is likely to match your customer’s needs. The customer will typically bring the sharpest focus on the business problem to the table, though may sometimes lack the technical depth of understanding needed to work effectively with you on the design. A customer who has plenty of time available to work with the design team and who understands the paper prototyping approach will add far greater value than any other approach. Without close access to this critical member of the team, the requirements can be misinterpreted as your feedback comes purely from the rest of the design and development team - often people who are less familiar with the business challenge at hand. We would absolutely recommend getting as much customer time as possible in this early, critical phase by including a number of signoff and review sessions designed to capture the design in as much detail as possible and as early as possible.

Once you have done a number of iterations of the paper prototypes with your team or your customer, it is time to move to the next level up and create a higher fidelity digital prototype.

The three main situations you want to use higher fidelity prototypes are when presenting concepts more formally to customers for signoff and approval, when testing with users for whom a higher quality bar is important and when handing over to development and QA alongside a detailed requirements specification.

The further up the management chain you go or the larger the project budget, the more likely the expectation for higher fidelity prototypes will be from the customer. In this case, it is likely you will paper prototype with your fellow design/development team before creating a higher fidelity mockup for management review.

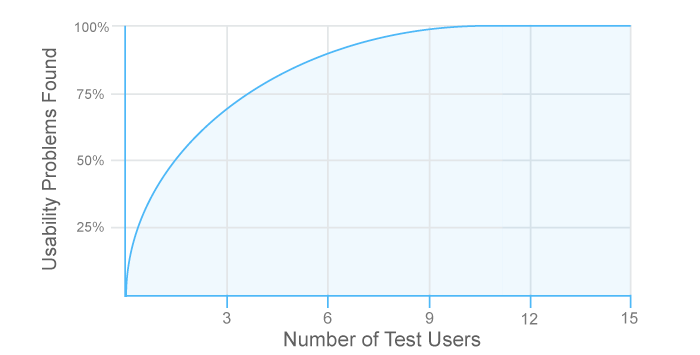

Testing with users should only happen after developing a higher fidelity prototype and should always come after you have gotten initial guidelines from your customer about the design (again, sometimes there is a crossover between customer and user and this is perfectly fine). The key point here is to ensure the business case is met before ensuring that the software is usable. When you do get to user testing, the Nielsen group recommends doing tests with no more than 5 end users of your prototype - suggesting that 85% of usability issues are uncovered with that many users.

While the people involved in each stage of the prototyping and design process might change, the fundamental process remains quite similar (moving from paper to digital and iteratively getting feedback at every stage), while you simply manage which fidelity to unveil at which time and to which groups.

We recommend having as much of the graphics and copy as complete as possible before handing over to developers (these can also be used by QA not only to build test cases, but to do pixel perfect reviews at a later date). We believe in never using placeholder text when doing later stage digital prototyping (though there are many diverse opinions on this). I’ve simply seen too many delays, rework and “programmer language” make it into production code because of not doing the boring copy work at the right time (i.e. early in the project).

One other benefit happens when you are doing user tests. The more you can focus on the exact wording and functionality, the less time you will need to explain functionality and the less the user will have to imagine how things work. This in turn reduces their suspension of disbelief, giving you better feedback on a real world prototype. Without having accurate copy in your prototype, you are doing yourself a disservice in not capturing the best possible feedback, all because the same body of work that needs to be done anyway is being done in the wrong order.

The more feedback you can get before handing over to development, the better your design will be, but more than 2-3 iterations of paper and digital should be enough for most software projects. After that, it is likely that time and budget factors will push the design into production anyway in order to keep the project moving forward. The design will never be perfect no matter how hard you try anyway, especially as other parts of the product evolve and more and more users use the product in the real world for unintended consequences. The balance of creating a great design now shifts from exploring ideas to executing and creating a functional product.

At this stage, assuming you’ve followed the paper and digital prototyping process, you’ll have iteratively created a design that has gotten feedback from your fellow team members, customers and users at multiple stages during the process, and all before a single line of code has been written - one of the key indicators of a project that will both be delivered on time and please the users that use it.

As the designer, you’ll continue to be involved in clarifications and low level design details, but ideally, your primary role is complete and you will be able to enjoy a well earned coffee before moving on to the next sprint or project safe in the knowledge that you have captured and signed off on the requirements in a well understood and well communicated way that will bring delight to the users that are affected by your choices every day.