In a recent reshuffle at Apple, Jonathan Ive (the industrial design brain behind products such as the iMac and iPhone) took on responsibility for Apple’s “human interface” design. His growing influence in the world’s largest technology company is the best example of a recent trend where industrial and software design are coming together to form a single unified design process. When we consider some of the awful designs of the recent decades, there is no doubt that this is a great development for users, but maybe one that should never have needed to happen.

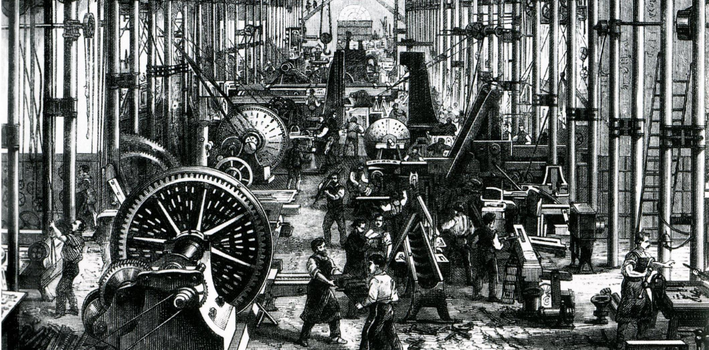

The seeds of the split were sown at the dawn of the industrial revolution. The inevitable march of progress saw assembly line workers replacing the age old traditions of master craftsmen. Growing demand soon meant it was impossible for any one person to deliver the range and quality of products that were being demanded by an ever more affluent and better educated consumer. New job roles and new expertises were needed, and the job of industrial designer was born.

There was no single place where it all began. In the UK, the craftsman coexisted happily with production lines until railways allowed goods to be transported all across the country. In America, industrialists like Henry Ford popularized concepts such as efficiency, standardization and functionality and this approach helped to create other beautiful products like the Kodak camera and the Singer sewing machine.

In 1907, the Deutscher Werkbund was founded in Germany by designers, architects and industrialists seeking to combine traditional crafts and industrial mass-production techniques. This led to the Bauhaus movement, a state-sponsored effort to put Germany back on a competitive footing with other nations. The design principles forged during this time and later by Dieter Rams became the basis of modern industrial design.

As the 1950s came to a close, household appliances began to flourish and the microchip was invented. Faced with a choice between the familiar world of hardware and the new world of software, industrial designers stayed their course, leaving UI design in the hands of engineers. Innovation became valued above usability and the physical form and user interface became separated.

Throughout the 80’s and 90’s, design went from the “less is more” mantra to ugly, complicated, multi button interfaces, exemplified by the often horrendous designs of everyday objects like the TV remote control.

Credit has to be given to Motorola as the first company to start producing phones which once again focused on the user. With the release of the StarTAC, users could comfortably use the device with one hand and its distinctive clam shell design bridged form and function better than its predecessors. It was relatively light, smaller in size than other mobile phones, and its longer lasting battery made it one of the biggest selling mobile phones of its era. In 2005, PC World Magazine named the StarTAC as one of the 50 greatest gadgets of the past 50 years.

Since the success of Motorola and those that followed, the relationship between HCI, product design and industrial design has become better understood. The ever growing sprawl of technology necessitates that designers create new ways of dovetailing software with hardware. Companies that succeed in creating great experiences such as Nokia, Apple and Samsung win consumer’s hearts, maintaining a significant competitive advantage in terms of desirability and marketability.

The 10 industrial design principles curated by Dieter Rams, now applies to software design just as much as hardware and the relationship between designing amazing user experiences and successful software products is finally being understood.