I visited the Design Council as part of a week long course on Design Thinking and Innovation with the Future London Academy. Prior to the week, I hadn’t really given a great deal of thought to design thinking. I had heard about it but always thought it was so obvious that it was hardly worth talking about. As the week unfolded I began to wonder why design thinking doesn’t play more of a part in conversations about most aspects of life.

It would be easy to say that design thinking is far more about ‘thinking’ than it is about ‘design’ and that is something that did strike me on a couple of occasions. But the visit to the Design Council where we met with the director of design, Clare Devine altered my perspective. Design thinking is not a clever idea at all. It is an idea that makes perfect sense but one which has been ignored by many. Let me give you an example.

Not shared paths. Not shared with cars and definitely not shared with pedestrians. Cycle paths. Dedicated and segregated. Joined up and connected. Space for cycling.

Some readers will think ‘this all sounds fairly logical’, but Ireland has one university campus under construction inside the canals in Dublin without a single sign of a cycle path.

Let me give you another example. Recently, in a local university where one of the buildings was being extended, a new path was needed around the building. Simple enough you might imagine. However, at one point the path is interrupted by a green space which was placed in front of the new building.

The red dotted lines are the proposed footpaths which ran around the new building. So far so good. What then is the circle you might reasonably ask. Interestingly enough the circle was a later addition to the plan. It was added on a bit of a whim as someone thought that it would be a good idea to put a green space in front of the new building. Nothing wrong with green space. Unfortunately, there wasn’t a lot of thought put into the impact of this decision. A university has a lot of students walking around from lecture to lecture and they are often rushing. While it would only take a few extra seconds to circumvent the green space, this proved to be an unpopular option. The vast majority simply walked straight through the green space which meant that it was worn away within weeks. The college authorities relented eventually and redesigned the footpath to meet the needs of the students.

In Book 4 of Dante’s Inferno, we meet some of the great philosophers of ancient Greece and Rome. It begins with a reference to an unnamed philosopher who appears to be revered by the others:

Then, having raised my brows a little higher, the Teacher I beheld of those that know, seated amid a group of philosophers. They all look up to him, all honor him.

The unnamed philosopher was Aristotle whose influence on western thought cannot be measured. More importantly to our theme, he had already looked at the importance of design thinking. He use rhetoric to prove that it was in opposition to analytical thought.

“The western world bought the wrong thinking system from Aristotle,” Golsby-Smith argues. “Aristotle conceived two thinking systems, not one. We made the mistake of just buying one, and then allowing it to monopolize the whole territory of thought. We should have bought both and used them as partners.”

The first thinking system, which laid the foundation for western scientific thought, is what we generally refer to as deductive reasoning, analysis, or logic. (If a=b, and b=c, then a=c.) The second thinking system Aristotle discussed was a more open-ended process of supposition, hypothesis generation, and argument, which he called rhetoric.

While it is clear that Aristotle certainly had a handle on design thinking, it is clear that Winston Churchill also had similar ideas. Even as the Second World War raged, he was able to see the bigger picture and look to build a future for the UK. It is interesting to note that the Design Council was the result of his perspective.

Success is stumbling from failure to failure with no loss of enthusiasm.

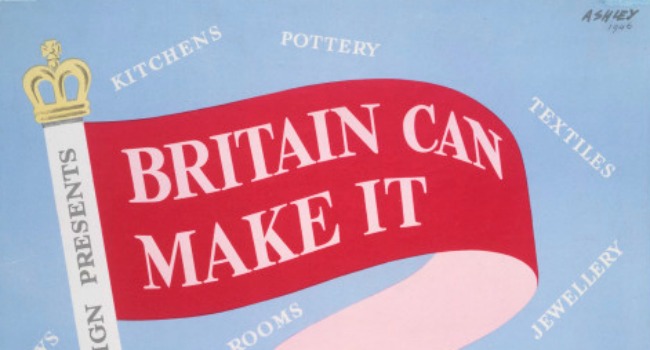

The Design Council was set up in 1944 with a clear objective which was to use design to promote the revival of the British economy. It began as a way to drive the economy. Very quickly the importance of a design element began to take hold. By 1946 the impact of the Design Council became clear when an exhibition was held at the Victoria and Albert Museum entitled Britain can make it.

The Furnished Rooms Section at BCMI 1946 allowed the public a glimpse at the possibilities of better designed postwar housing, unconditioned either by the increasingly uncomfortable reality of the government’s inability to solve the housing shortage or by the lack of significant design intervention in the majority of British manufacturing industry.

As several experts talked about and explained design thinking it became clear to me that they were talking about a term which I knew already but under a different name or even names: lateral thinking, blue-sky thinking, thinking outside the box. It is an idea that can be traced all the way back to Aristotle. Each of the approaches has one crucial aspect in common: perspective. By changing one’s perspective it is thought possible to take a fresh approach to an old problem. For those who might be a bit sceptical it is interesting to note that Google have recently set up a new research project under the title ‘Project Aristotle’ .

The evolution of the Design Council gives us a good insight into the evolution of design over the last seventy years. Whereas the Design Council was set up in 1944 to demonstrate the value of industrial design in reviving post-war Britain. Over the years it has evolved and now has an even wider remit championing the use of design and design thinking as a way to improve the lives of all citizens.

In researching this blog post, I came across some articles from fervent advocates of design thinking which had placed some question marks over its future.

They did provide an insight into why design thinking can work very well and why it can at times seem to not work at all. Two posts in particular came from Bruce Nussbaum and Helen Walters. Both were very well known writers on the subject and it was difficult to dismiss their views.

When I looked a bit more closely at the rationale behind the view that design thinking was to use Nussbaum’s words:

Design consultancies that promoted design thinking were, in effect, hoping that a process trick would produce significant cultural and organisational change.

The problem was and still is not with design thinking. The problem is with organisations that think that design thinking is a ‘miracle cure’ to use Walter’s words.

What does the Council do now and why it is so important? The Design Council fosters an environment in which design is an integral part of any project. It does not matter what the project is: whether it relates to business growth, service transformation or the built environment, design principles need to be given sufficient room.

The fundamental core of the approach taken by the Design Council when they are tasked with a project is always the same. There are two stages in what is known as the Double Diamond Methodology.

Data collection

It is a capital mistake to theorize before one has data. Insensibly one begins to twist facts to suit theories, instead of theories to suit facts.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, A Scandal in Bohemia

First, gather sufficient data from key stakeholders and service users. This makes it possible for the project team to isolate the correct problem that needs to be solved.

Develop and deliver a solution

The process starts upon the supposition that when you have eliminated all which is impossible, then whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth. It may be that several explanations remain, in which case one tries test after test until one or other of them has a convincing amount of support.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, The Adventure of the Blanched Soldier

For example, the Design Council were approached in relation to an NHS project which sought to reduce the number of mixed gender wards. Having talked to stakeholders and users of the service it became clear that the mixed gender wards was not the problem at all. There were other issues such as inappropriate hospital gowns which were of far more concern to users and turned out to be the real problem that needed to be addressed. It was only by applying and sticking to their used and tested methodology that the correct problem could be identified and the correct solution arrived at.

Before my week with the Future London Academy, I had not really given any thought to the reason why London was a centre for art and design. After my visit to the Design Council, the reason was glaringly obvious. Once you identify the right problem, arriving at the solution is only a few iterations away.